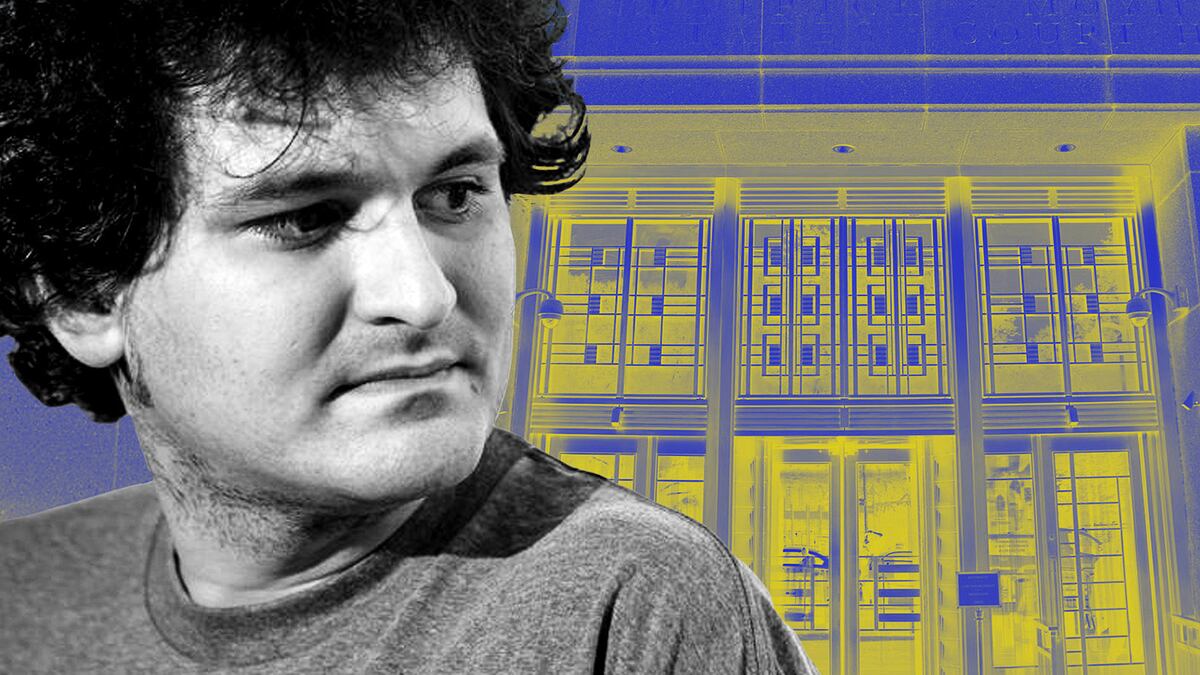

- Sam Bankman-Fried is facing a maximum sentence of 110 years after his fraud trial ended on Thursday.

- The case was full of surprises, most notably, its speed.

- Here's what the judge will weigh in setting his prison term.

Ari Redbord, a former federal prosecutor, is the global head of policy and government affairs at TRM Labs, a blockchain intelligence company. Views expressed are his own.

The Sam Bankman-Fried case will be remembered for the scale of its $10 billion fraud and the epic fall of a crypto wunderkind. To me, though, the case will be remembered for something else — its unprecedented speed.

After less than five hours of deliberations, 12 jurors unanimously found Bankman-Fried guilty of seven counts of fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy. This is Formula 1 speed for a jury considering that many charges in a complex finance case.

Nine months

Then again, it only took about a month for a grand jury to indict Bankman-Fried after the November 11, 2022 bankruptcy of FTX, the crypto exchange he founded.

The trial, which commenced on October 3, began exactly nine months and 20 days after Bankman-Fried was arrested in the Bahamas. Bankman-Fried and his management team ran FTX and Alameda Research, an investment fund, from a $35 million penthouse in the Caribbean nation.

That means in about nine months, prosecutors managed to extradite Bankman-Fried to New York to stand trial, negotiate cooperation agreements and take guilty pleas from three key cooperating witnesses, dig through a mountain of electronic evidence, and synthesise and simplify arcane crypto and blockchain concepts for the ordinary citizens who would form a jury.

Bankman-Fried’s defence lawyers, of course, also prepared for a seemingly impossible case on their side.

The trial itself was fast. What was projected to be seven weeks of hearing evidence, and could have been 12 based on the number of witnesses and exhibits, took only five.

And then there was the verdict. For a complex financial crime case, the speed of the jury’s deliberations was a surprise for this former prosecutor. Even in a really strong case, one or two jurors often want to push the rest of the panel to more closely consider the evidence, review transcripts, and ask questions of the court and the lawyers on both sides.

Home for dinner

Juries closely read the judge’s instructions and then take a straw poll on the defendant’s guilt or innocence on each count. Usually there are at least one or two holdouts. Given the speed of the verdicts in the Bankman-Fried case, there was most likely almost complete agreement after the first round of polling.

Perhaps the jury looked at a piece or two of evidence, but there was not time for much more. They filled out the verdict form and were home for a late dinner.

One thing that will not go as quickly is Bankman-Fried’s time in prison. The defendant, who is only 31, is staring down the barrel of a maximum term of 110 years.

Federal courts largely rely on the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. While no longer mandatory, federal judges look to the guidelines when crafting sentences.

In weighing a sentence, US District Court Judge Lewis Kaplan will consider the amount stolen, the number of victims, the substantial hardship caused, the sophistication of the crime, the fact the offence involved financial institutions, and other potential factors.

Benefit of the doubt

When Bankman-Fried is sentenced next March 28, he will not likely be sent to prison for life, but he will do significant time.

While his co-conspirators quickly pled guilty and moved fast to accept responsibility and cooperate with the government, he lied and denied and forced the government to go to trial.

He will, therefore, not get the benefit of the doubt from the government or the court.