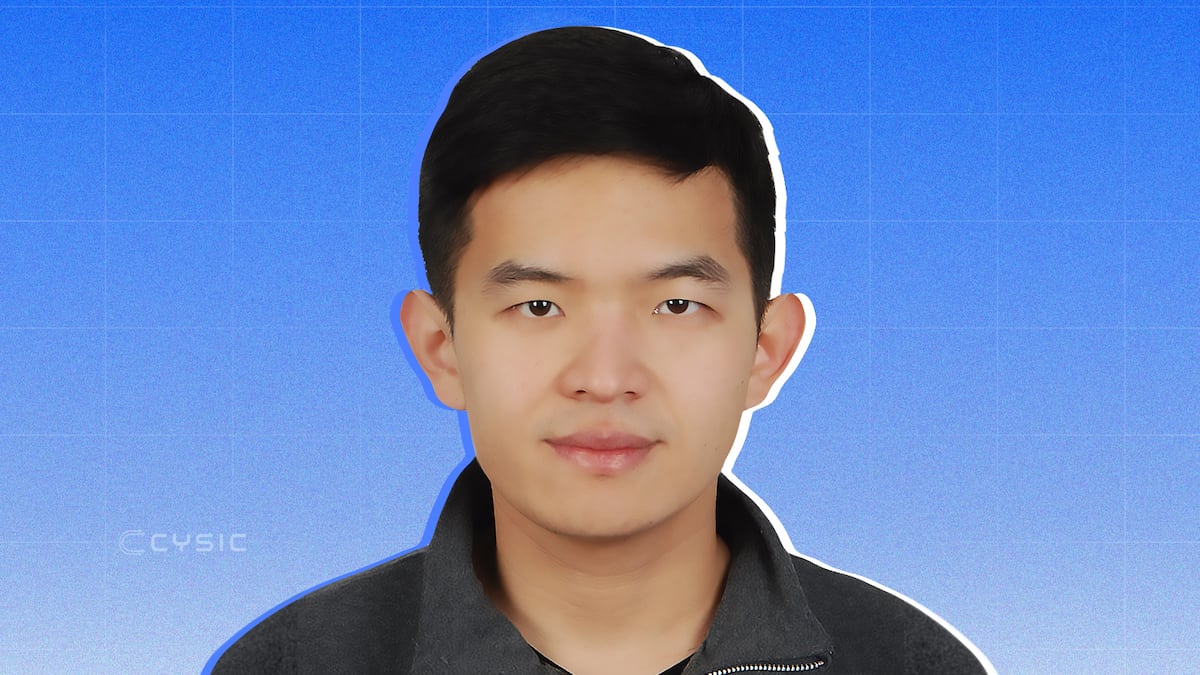

Leo Fan is the Founder and CEO of Cysic, a full-stack compute infrastructure network that powers verifiable AI and zero-knowledge computation. He earned his PhD in Computer Science from Cornell University under Professor Elaine Shi, specialising in cryptography, formal methods, and verifiable systems.

Before founding Cysic, Leo served as an Assistant Professor of Computer Science at Rutgers University and conducted research at institutions including Algorand, IBM T.J. Watson Research Centre, Bell Labs, and Yahoo Labs.

A recognised leader in hardware-accelerated zero-knowledge proving, Leo organised the industry-wide ZPrize competition to advance ZK performance. At Cysic, he bridges cryptographic research, silicon design, and blockchain protocol engineering to transform compute into a programmable, verifiable onchain asset class.

We caught up with Leo Fan, Founder of Cysic, at Consensus in Hong Kong last week to discuss bottlenecks in zero-knowledge proof generation and his vision for a decentralised compute economy.

Read more about how Cysic is reducing proof generation times from hours to minutes in the interview below.

You trained as a cryptographer at Cornell under Elaine Shi and spent years working on formal methods and verifiable systems. What was it about ZK proofs that caught your eye?

My PhD training provided a comprehensive foundation across the entire cryptographic landscape. While my primary research focused on encryption rather than zero-knowledge proofs specifically, I understood the underlying mechanics thoroughly.

My time at Algorand bridged the gap between theory and practice. We built ZK bridges connecting Algorand to Solana and Ethereum.

That production implementation revealed a critical bottleneck. We discovered that proof generation was prohibitively slow for real-world applications. That specific challenge became the inspiration for Cysic.

You have published in top-tier security and systems venues and worked at places such as Algorand and IBM Research. What did academia teach you about building a secure system that most crypto startups overlook?

Academia instils a systematic approach to security that begins with a precise definition. You must identify exactly which properties are necessary and exclude everything else.

Once you have a construction, the immediate next step is to attack it relentlessly. The first draft always contains loopholes, so we iterate until the fifth or sixth version resists every attack. This adversarial process ensures we understand the system inside and out.

Only then do we move to the proof phase. We anchor the system’s security in a hard mathematical assumption, such as “learning with errors.” This guarantees that breaking the system would require breaking the underlying math itself. That is the essence of provable security.

You organised the ZPrize competition to accelerate ZK hardware performance. Was Cysic born out of what you learned during ZPrize about the industry’s bottlenecks?

Actually, we started Cysic before the ZPrize, right after 2022. We wanted to participate, but it was too late to register. So we created our own solution, and at that time it was faster than all the teams in the prize.

Since we performed so well, the community thought we were quite knowledgeable. They asked us to organise and architect the ZPrize 2023. We evaluated two tracks, focusing on using hardware such as GPUs and FPGAs to accelerate specific kernels and the end-to-end process for hash functions such as Poseidon.

What convinced you to leave academia and build infrastructure at a production scale?

My academic background is in theoretical cryptography. However, the most rewarding aspect is seeing abstract theory applied in practice. It confirms that our work generates tangible, real-world impact. This bridge between theory and reality is what excites me most.

With Cysic, you’re integrating silicon design, cryptography, and blockchain coordination. Why does Cysic require full-stack control?

Having full-stack control allows us to extract more value from the process. Right now, if we are missing one component in the loop, such as the silicon parts, we have to buy hardware from Nvidia or other major manufacturers.

We pay them a lot for the hardware. The actual cost of a GPU might be around $700, but they sell it for $2,000 or even $3,000. That is a big difference. Having full control allows us to extract the most value from the entire loop, from manufacturing through to implementation.

When you designed Cysic’s layered architecture, which constraints came from theory and which came from hardware realities?

In theory, there are few limits. In practice, take ZKML as an example. ZKML combines ZK and machine learning to certify results from inference or training. Even with a very powerful server, such as a 5090 GPU, certifying the GPT-3 inference process takes about 10 seconds.

And that is not even GPT-5. If we want to certify larger models, it takes much longer on commercial hardware. We are still exploring how to put ZKML into practice. We want to build specialised chips to handle this scenario and make the latency tolerable for people.

You describe ComputeFi as the financialisation of compute. What does that mean beyond a slogan?

ComputeFi is the main narrative right now. It means we want people to put their idle devices into the Cysic Network to contribute to the community. The key difference is that we are not just a platform matching buyers and sellers. We are moving much deeper.

For instance, in a ZK project, proof generation without our software takes one hour and 45 minutes on a large database. With our CUDA software and GPU acceleration, we can reduce that time to 15 minutes on a two-card 4090 setup.

Using this software, we can bring more people to plug in their idle devices. They receive rewards in our tokens or our partners’ tokens. In this way, people have more incentive to use their idle hardware in Cysic.

Cysic was designed as a Cosmos CDK L1 with EVM compatibility. What did that unlock that coordinating compute on Ethereum or Solana would not?

Ethereum remains the most active ecosystem. People are developing many interesting applications on Layer 2s and side chains that require significant computing power. Cysic is providing the computing power for all of them.

However, we are not exclusive to that. We still support Solana-based projects that require high hardware performance and computing power.

In traditional PoS, capital secures the network. In PoC, compute also influences consensus. How do you prevent compute centralisation from becoming governance centralisation?

In my opinion, the people who have a high stake in our token and those with high computing power are two different groups. Previously, I was a BTC miner. I just mined BTC and stored it in a cold wallet.

The purpose of having Proof of Compute (PoC) is to add another layer on top of Proof of Stake. We want the machines that truly contribute their computing power to the Cysic network to have a say in voting and governance.

In that way, centralisation can be avoided. We are still closely monitoring our ecosystem and will make the necessary upgrades to the consensus if centralisation occurs there.

You mention a multi-proof approach using ZK proofs and TEE attestations. Do you expect ZK to eventually replace TEE-based verification?

Eventually, yes. The current compromise is that ZK is not fast enough. In the previous example, certifying the inference of recent models such as GPT-5 takes tens of seconds, which is unacceptable.

But if you break the process into chunks, some of them might not involve user data. For those parts, we can use Trusted Execution Environments (TEE) to certify the process. If we combine TEE with ZK proofs, we can significantly reduce time, perhaps from 40 seconds to 6 or 8 seconds.

TEEs rely on trust in major manufacturers such as Intel or AMD, and side-channel attacks are regularly found. ZK is more secure but currently less performant. We use TEE for the data-sensitive parts to deliver a product that users can accept today.

Your ZK C1 chip claims to deliver 10 to 100 times the efficiency of GPUs. Where exactly does that gain come from?

The gain comes from the chip’s specific design. Since our chip is used only for generating ZK proofs, we can optimise for that very narrow scenario much better than a general-purpose GPU.

The gain comes from specific designs, such as high bandwidth. We use 3D stacking, which effectively places one chip on top of another. This creates a much wider channel for data transmission compared with traditional designs.

By tokenising hardware via Node NFTs and ASIC RWAs, where does the value accrue? How does Cysic ensure rewards reflect real compute demand?

The value accrues from all the partners working with Cysic. We provide end-to-end proof generation for them. We receive the data, generate the proof, store it on our chain, and send them a digest. It is a JSON-to-JSON process.

Because we provide this end-to-end service, many projects want to work with us. The value for the NFT or RWA holder comes from the demand generated by this entire process.

If you had to summarise your thesis in one sentence, why does the world need a decentralised compute economy?

There is always a risk of server outages. Although networks such as Ethereum, Starknet, or Solana claim to be decentralised, they often rely heavily on AWS, particularly the Virginia data centre.

If a malfunction occurs at that specific data centre, it affects all these chains. We provide decentralised hardware. We ask people to plug in their power, and the blockchain assigns tasks based on reputation.

If they are reliable, have high uptime, and have a large stake, they receive more tasks. In that way, we are using decentralised power to solve a centralised infrastructure issue.

What would success look like in five years? Liquid compute markets? Compute derivatives? Standardised pricing benchmarks?

I would say all these things are indicators of success in a computing future. We are currently in a very early stage. We want to standardise components and encourage people to use our software.

We are reaching out to customers to encourage them to use our hardware because it is cheaper and faster when combined with our software. As more projects come into our system, it attracts more hardware providers. With more hardware, we can support more projects. That is how the flywheel works.